Biography of the President

The Early Years: From Childhood to Graduation

"The Einaudis come from the Maira valley, above Dronero1; and

there you can count more Einaudis than stones: since time

immemorial, all mountaineers, woodcutters, shepherds and farmers"

From a handwritten letter by Luigi Einaudi dated 5

September 1953

Luigi Einaudi was born in Carrù (Cuneo) on 24 March, 1874, to Lorenzo

a tax collection service concessionaire, and Placida Fracchia. Luigi

attended his primary school in Carrù and high school in Savona. In

1888, after his father’s death, the family moved to Dogliani, his mother’s

hometown, where he lived in the old family home: "These habits that I

observed in the ancestral home were the universal habits of the

Piedmontese bourgeoisie for much of the 19th century; and at a time

when social climbing was not frequent, one can understand how those

habits moulded a ruling class who left deep traces of honesty, ability,

thrift and devotion to duty in the political and administrative life of the

Piedmont that made Italy...". In 1888, Luigi attended the Classical

Lyceum in Turin. In 1891, he enrolled in the Faculty of Law at the

University of Turin to graduate with full marks in July 1895 with a thesis

on "The Agrarian Crisis in England", supervisor Professor Cognetti de

Martiis.

1 t/n: In the North-West of Italy

Public and Private Life: Assistant and Professor, Husband and Father

"At the age of thirty-four, Luigi Einaudi was a Public Finance

teacher. He gave lectures at eight o’clock in the morning. He

gathered undergraduates and young economists around him,

many of them would later become Masters ... Rarely have I heard

a word that penetrated so much, lectures whose words are still

remembered more than half a century later".

Arturo Carlo Jemolo, Anni di prova, 1969

After graduating, Einaudi became an "unpaid university professor

assistant". In 1898, he was awarded the certification for teaching

Political economy. In 1899, he won the competition for the Chair of

"Economics, Finance and Statistics" in secondary technical schools. He

taught at the Bonelli then at the Sommeiller secondary technical schools

in Cuneo and in Turin. In the meantime, he began his university career

on an independent teaching. In 1902, at the age of 28 only, he won the

competition for Public Economics called by the University of Pisa. There,

he was appointed professor of Public Economics and Financial Law

under a temporary contract before being transferred to the Faculty of

Law at the University of Turin, which was to become his permanent post.

On 19 December 1903, Luigi married Ida Pellegrini in Turin. She was

the eighteen-year-old daughter of a nobleman from Verona who had

moved to Turin on business. Three children were were born from the

marriage, Mario (1904), Roberto (1906) and Giulio (1912) as well as

Maria Teresa and Lorenzo who died prematurely.

The family split their time between Turin and Dogliani, a place in the

countryside where Luigi had bought the S. Giacomo farmhouse, the

basis of a property which he extended and improved over the years.

The Scholar of Economic History and Finance Law

Italian economics "was second to none". The book Principi di economia

pura by Maffeo Pantaleoni (1889) constituted the "point of reference - a

gem". Barone "showed Walras how to do without the constant

coefficients of production". "The kind of general economics that may be

represented by the work of Luigi Einaudi". "Finally we reach that peak

which was Pareto".

Joseph A. Schumpeter, History of Economic Analysis, 1954, Vol. III, Ch. V2

Einaudi’s first book, "Il Principe mercante" (The merchant prince) was

published in the year 1900. There, Luigi Einaudi drew the portrait of a

successful Italian textile entrepreneur. The young liberal scholar praised

the work of Italians who had "come up through hard work and courage,

from humble labourers, to prominent economic positions". He magnified

"self-made men" who were the "living embodiment" of "intellectual and

organisational qualities", those "eminent individualities who were able to

[emerge] from the grey and anonymous crowd by greatness of intellect,

by daring enterprise or even by a fortunate combination of favourable

circumstances". In 1900, he also published "La rendita mineraria" (The

mining income), a challenging study published within UTET’s prestigious

"Biblioteca dell’economista" (Economist’s Library). In 1902, he

published his third monograph: "Studi sugli effetti delle imposte.

Contributo allo studio dei problemi tributari municipali" (Studies on the

effects of taxation. A contribution to studying Town taxation issues). All

these writings ensured that, by the early 20th century, young Einaudi not

yet in his Thirties years of age,was an established exponent of the most

prominent Italian economic science, particularly in the field of Fiscal

Finance. Together with Pantaleoni, Pareto, Barone, de Viti de Marco and

Ricci, he was and would remain one among the Italian economists

deserving international prestige. In the years that followed, he

conducted important research on the History of finance under the Savoy

monarchy as well as studies on Financial Law: "Intorno al concetto di

reddito imponibile e di un sistema di imposte sul reddito consumato" of

1912, (Around the concept of taxable income and of a taxation system

based on consumed income) a fundamental work on the core of issues

he had been addressing since 1909 on the topic of earned and

consumed income; and "Corso di Scienza delle finanze" (Course on

Financial Law)Cof 1914. Thanks to the sound reputation he had

acquired, Einaudi collaborated as a columnist first with "La Stampa"

(from 1896), then with Corriere della Sera (from 1903); in 1908, he

began a collaboration with The Economist which went on until 1940.

2 t/n: quotations from http://digamo.free.fr/schumphea.pdf

The "Social Reform" and the "Turin School of Economics

"Without changing its name, "Riforma Sociale" gradually changed

its orientation; it began appreciating more the classical economy

and, while not neglecting the problems of reforms in the

distribution of wealth, it began insisting more on the problems of

convenience in production and the fight against the many kinds of

protections, constraints and monopolies …"

Luigi Einaudi, Preface to Francesco Saverio Nitti, Scritti sulla questione meridionale, 1958

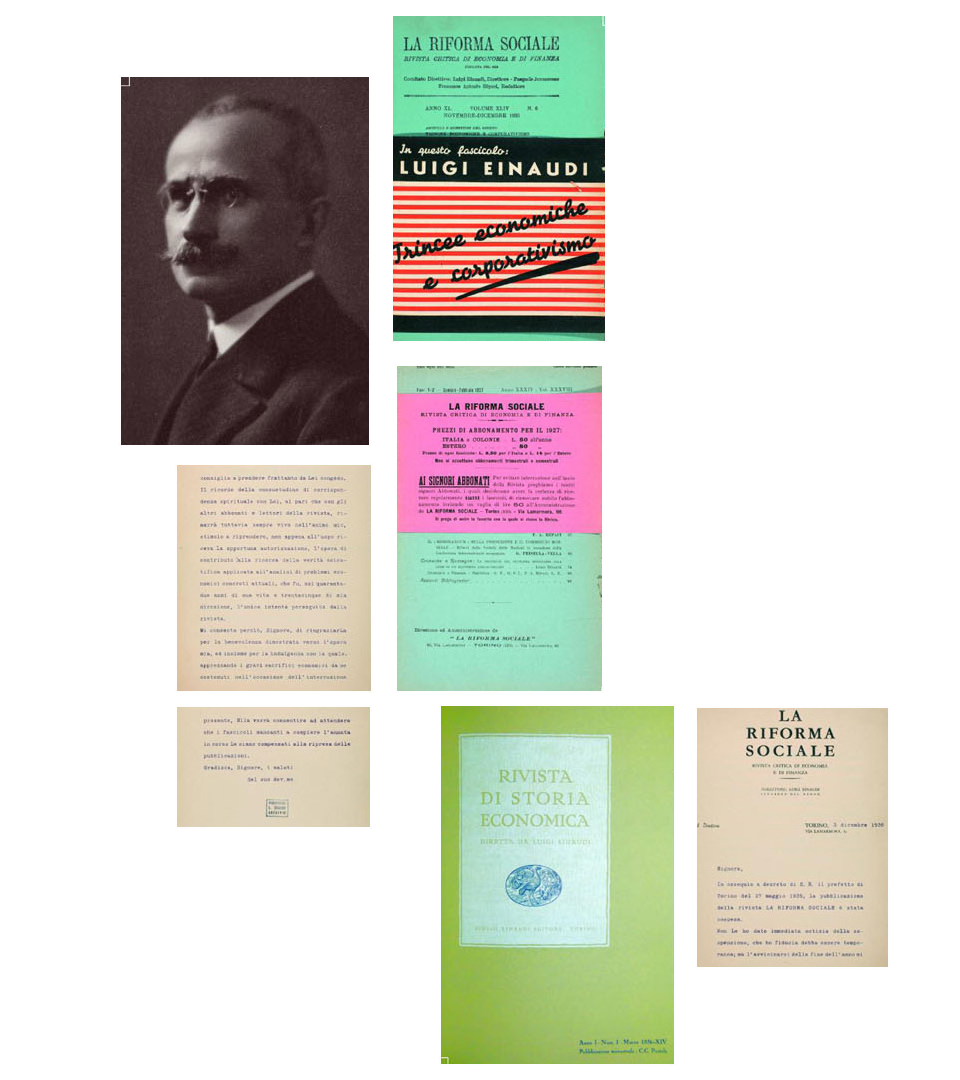

In 1908, Einaudi became the editor of "Riforma Sociale". The journal

had been founded in 1894 by Francesco Saverio Nitti and the Turin

publisher Luigi Roux. They intended to give their contribution in tuning

the Italian liberal institutions to the dynamics and conflicts of the

emerging industrial society. Under Einaudi’s guidance, "La Riforma

sociale" proclaimed a liberal, classical and reform-oriented vision at the

same time, a legacy from the great English and Italian tradition of John

Stuart Mill and Cavour. An entourage of valuable collaborators built up

around Einaudi. They would become the core of the "Turin School of

Economics" whose doctrine and originality would receive wide

recognition in the following years. Together with Pasquale Jannaccone

and Giuseppe Prato, respectively co-director and editor-in-chief of "La

Riforma Sociale", Attilio Cabiati joined the school when moving to Turin

at the beginning of the century.

From the Great War to Fascism: 1914-1926

"Woe betide whomever fell from the natural aspiration to liberate

from the bestial civil war into which the political struggle of Italy

had degenerated between 1919 and 1921, into absolute

conformity to the nationalistic gospel imposed by fascism without

contrast! This would be the death of the nation".

Luigi Einaudi, Preface to J. S. Mill, Liberty, 1925 3

At the outbreak of World War I, Luigi Einaudi was on the interventionist

side of the Entente. In this period and in the immediate post-war period,

Einaudi’s thinking was characterised by a strong ethical and political

tension and by a particular focus on international issues. Two famous

collections bear witness to this: the "Lettere politiche di Junius" (1920)

(Junius political letters) and "Gli ideali di un economista" (1921) (The

ideals on an economist), where he outlined his "ideals": "the educational

school, England, the unification of Italy through the history of Piedmont,

the need for supernational governments". During the war, Einaudi was

called by Filippo Meda, the Finance Minister in the Boselli government

to take part in a parliamentary commission charged with the study and

preparation of the tax reform. He played a primary role in the drafting of

the project, which however was not implemented. On 6 October 1919,

he was appointed Senator of the Kingdom at the proposal of the Prime

Minister Francesco Saverio Nitti. One year later, he was appointed

director of the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences at the Luigi

Bocconi University in Milan, a post he held until 1926. The "biennio

rosso" (1919-1920) characterised by the revolts by peasants and

workers to occupy land and factories was interpreted by Einaudi as a

period of regression of "civilisation" and laceration of the social fabric. In

this context, Einaudi hoped that fascism would restore order. He shared

with other liberals the illusion that the new regime could then be brought

back into the structure and institutional dynamics of the liberal state. At

the end of 1923 "La bellezza della lotta" (The beauty of struggle) was

published: an effective synthesis of Einaudi’s liberalism to preface "Le

lotte del lavoro" (1924) (Struggles for labour). After Giacomo Matteotti

was murdered, the political situation deteriorated quickly in Italy. On 6

August 1924, Einaudi launched his cry of alarm in the article "Il silenzio

degli industriali" (The silence of industrialists). On 5 December, he voted

against the draft budget of the Ministry of the Interior for the 1924-25

fiscal period. In 1925, he published the Preface to John Stuart Mill’s

Freedom. There, he warned: "Woe betide whomever fell without

contrast from the natural aspiration to liberate from the bestial civil war

into which the political struggle of Italy had degenerated between 1919

and 1921 into absolute conformity to the nationalistic gospel imposed by

fascism! This would be the death of the nation".

On 1 May 1925, the Manifesto of Anti-Fascist Intellectuals drafted by

Benedetto Croce was published. Einaudi was among the first

signatories. On 28 November, he resigned as a contributor to the

Corriere della Sera following Luigi Albertini’s forced resignation from the

editorship and the new ownership of the newspaper by the Fascist-

friendly "F.lli Crespi e C.". In 1926, he was ousted from teaching at

Bocconi and at Polytechnic of Turin, again for political reasons.

3 t/n: in the Italian version of the text

A Professor Kept on the Edge, a Senator on the Sidelines

"In a way, Fascism is the result of the weariness which had gone

growing into the souls of the Italians after the long and furious

infighting in the post-war period. It is an attempt to regiment the

nation under one single flag. Souls yearned for peace, tranquillity,

rest. They were appeased by the word of those who promised

these goods".

Luigi Einaudi, Preface to John Stuart Mill, Freedom, Turin 1925 (Italian version)

In 1925 -1926, the regime forced Einaudi to sever two of his main

channels of communication with his audience: his collaboration with the

Corriere della sera, following the ousting of the Albertinis, and his post at

Bocconi where he had been teaching since 1904. He retained his

university professorship in the Faculty of Law in Turin, but to keep it he

had to submit to the odious obligation of swearing an oath of loyalty to

the regime imposed in 1931. Like many other anti-fascist professors, the

decision cost him no small torment. He went to Naples to see Benedetto

Croce who advised him to take the oath because otherwise he would be

replaced by a professor of fascist faith, and the students would be

educated in that faith. In the Faculty where he taught, Achille Loria and

Gioele Solari who were his friends and who had always sided with

reformist socialism also swore in this spirit.

The revival of the Riforma sociale and the Rivista di storia economica

"When facing real problems, the economist can never be either

liberalist, interventionist, or socialist whatever it takes; ... The free

man wants the State to intervene, just as the wise legislators of all

times and all countries have always intervened."

Luigi Einaudi

After 1922, the Riforma was seemingly losing its attractiveness. After he

was forced to leave Corriere della Sera, Luigi Einaudi threw himself

headlong into the task of giving a new thrust to Riforma. He acted in the

simplest way: by writing a whole set of articles on the Fascist monetary

policy in the second decade of the century. Actually, he shared the

strategy since inflation had been curbed and the exchange rate at

"quota 90" 4 had been successfully preserved. In the 1930s, came the

articles on the international economic crisis, the interventions on Keynes

and those on corporatism. In the three years following, the journal

became more pleasant to leaf through for the good taste of his son

Giulio who had become a publisher. Colourful Olivetti advertising had

been added together with a new modern printing style. With the closure

of Riforma Sociale in 1935, the regime cut short the life of a living,

breathing creature. Tirelessly, Einaudi founded the "Rivista di storia

economica" in 1936 (Review of economic history), with old and new

contributors. Through this erudite review, he continued to intervene on

contemporary problems, albeit indirectly and allusively.

4 t/n: in the fascist period Mussolini negotiated exchange rate 1£=90 Lit - before that was 1£=150Lit

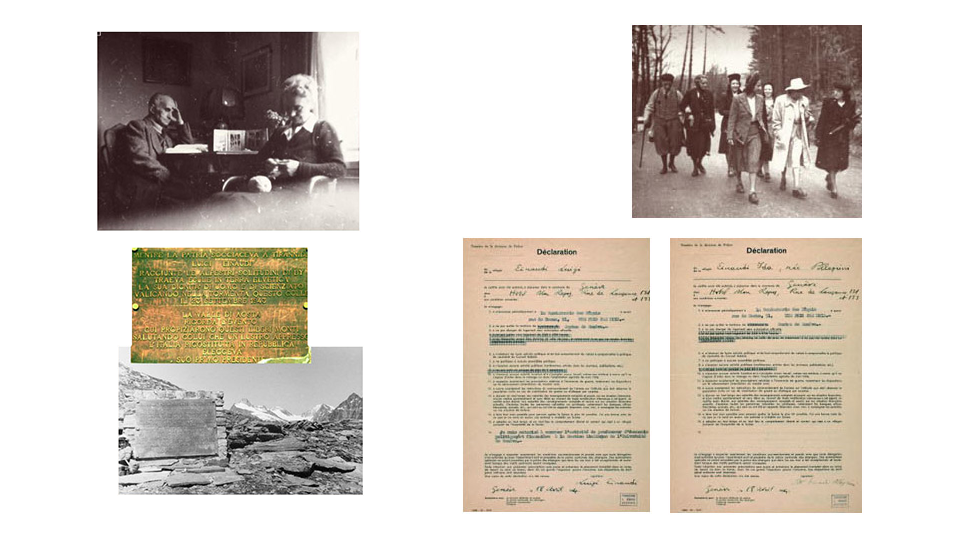

The Exile, across the Alps

The drama of the war and the consequent fall of Fascism created the

conditions for Einaudi to be reinstated to public life, even if only for a

short period. On 4 September 1943, during the 45 days of the Badoglio

government, Einaudi took up the post of dean at the University of Turin.

But already on the 22nd of that month, hunted by the Nazi-Fascists

occupying the North, he and his wife were forced to make a perilous

escape across the Alps. His diary maintains an impassive tone.

However his narrative is really engaging. At the border of Col Fenêtre,

he risked to be rejected: he was extremely cool when he told who he

was and gave he the name of his colleague from the University of

Geneva, William Rappard. The next day, they were in Martigny and then

in Lausanne. Also, they were blessed with the joy to meet their son

Giulio at the refugee camp where they had settled. This one had

crossed the border on 15 September, an officer in the Alpine troops. The

refugee Einaudi was no ordinary person. He soon left the Orphélinat

refugee camp. From Lausanne, the couple moved on to Basel in a small

flat where Margherita, the widow of one of Roberto Michels’s sons

hosted them. Luigi and Ida made a virtue out of necessity. Margherita

was a concert pianist, and perhaps for the first time in his life, Einaudi

approached chamber music with delight even though Cabiati jokingly put

it: "he founds the Royal March complicated". In April 1944, they moved

to Geneva.

The Swiss Experience

Over forty years earlier, Einaudi had been close to obtaining a chair in

Political Economy as Maffeo Pantaleoni successor in Geneva. Now, by

to his peer Rappard, he met some of the major Swiss intellectuals such

as the historian Werner Kaegi and the economist Edgard Salin. Roepke

taught in Geneva, at the Institut des hautes études internationales.

Another leading figure was the Swiss Plinio Bolla, promoter of a Comité

d’aide aux universitaires italiens en Suisse. In March 1944, Einaudi gave

a course to the Geneva university inmates, from there he derived the

bulk of the "Lezioni di politica sociale" (Lessons of social politics) of

1949. The most stimulating meetings were with Italians, first and

foremost Adriano Olivetti and Ernesto Rossi, a convinced federalist and

author with Altiero Spinelli of the Manifesto di Ventotene . Einaudi had

reservations about the radical tone of the Manifesto. Nevertheless, in his

article "Via il prefetto!" - published on 15 July 1944 in the supplement to

Gazzetta ticinese with the inspiring title "Italy and the Second

Risorgimento" - he expressed a condemnation without appeal against

the centralised and "Jacobin" state inherited from Napoleon, just as he

put an important assessment of the partisan movement, because of

those "bourgeois" who set out to reform the state from the bottom. The

immediate political contingency was not absent either: Einaudi was, in

fact, contacted by Maria José of Savoy to organise monarchist

propaganda, with a view to the institutional referendum once the war

would be over.

At the Helm of the Bank of Italy

Back to Italy, on 10 December 1944, Einaudi took up the post of

Governor of the Bank of Italy in early 1945. The country was facing

enormous problems. Inflation had exploded after the armistice of 8

September 1943 and the pricing system had broken down: between the

North and the South of the Country, between the city and the

countryside, between official prices and the black market. After the

Liberation, even if damage to manufacturing facilities seemed small,

damage to housing, to the transport and agriculture was enormous.

Even the Bank of Italy came out of the war impoverished in its assets

and with a weaker inner structure. The restoring of sovereignty and

monetary stability, the financing of reconstruction, the re-introduction of

the Lira and of the Italian economy into the new global context were the

major issues to be faced by Einaudi at the helm of the Bank of Italy and

then of the Government. Within his action, each one of these issues is

tied to his concern to restore an economy and a state being at the same

time the founder and the foundation of freedom for citizens.

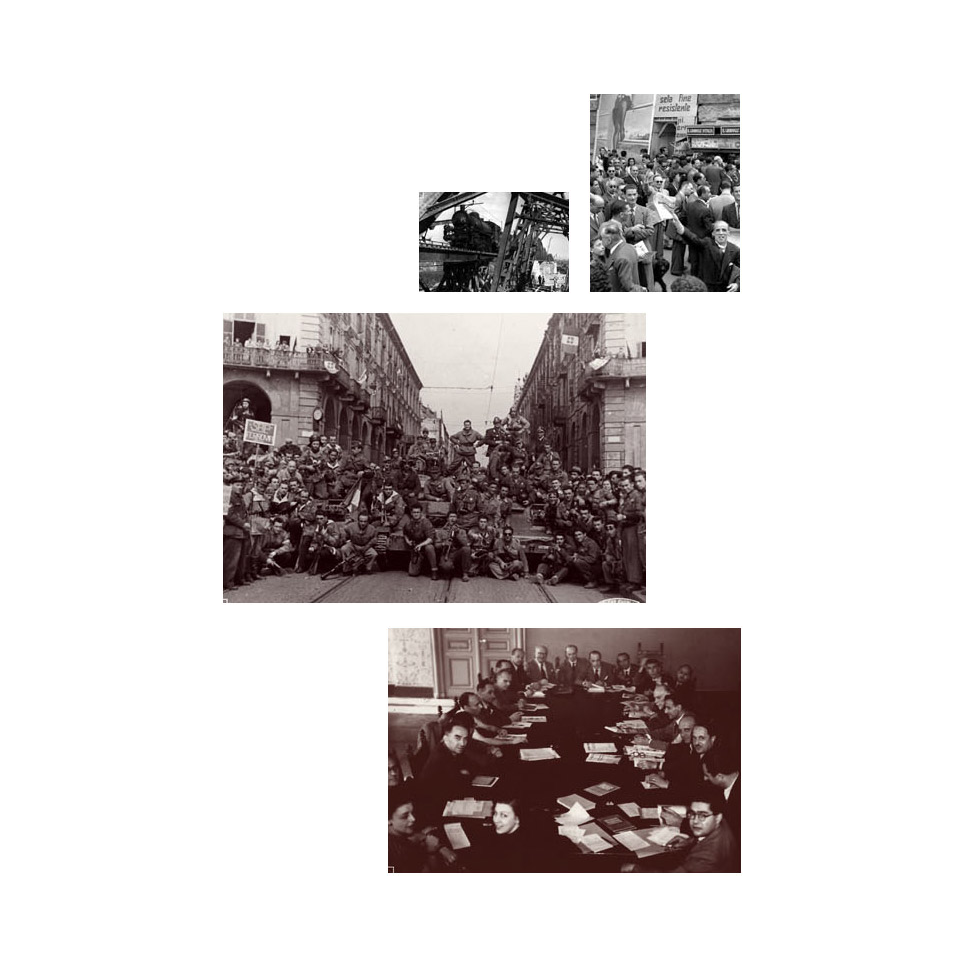

The Rebirth of the Italian Parliament

After the Liberation, Luigi Einaudi was appointed a member of the

Consulta Nazionale. Later, in June 1946, he was elected to the

Constituent Assembly as a Liberal in the list of the National Democratic

Union. Within the Constituent Assembly, he was a member of the

Commissione dei 75 - in charge of drafting a preliminary version of the

Constitution - and in the sub-commission on the constitutional order of

the State. On 31 May 1947, he joined De Gasperi fourth government as

Vice-President of the Council and Minister of Finance and the Treasury;

a few days later, on 4 June, he was replaced at the Finance by

Giuseppe Pella and at the Treasury by Gustavo Del Vecchio, to became

the holder of the new Ministry of the Budget while retaining his position

as Governor of the Bank of Italy. Einaudi’s parliamentary activity at the

Consulta and in the Constituent Assembly supported the transition from

Monarchy to Republic even if in the 1946 election campaign Einaudi

was in favor of the king due to his sub-alpine origin and also for reasons

of constitutional balance. As he was to recall after his election to the

Quirinal, Einaudi gave dozens of speeches to the Constituent Assembly

with "something more than loyal support". In his speeches to the

Consulta and the Constituent Assembly, Einaudi dealt with institutional

issues (electoral system, bicameralism, local autonomies), economic

and social issues (taxation system, international monetary system,

planning, monopolies, education), and international issues (Europeism

and peace). Even though Einaudi had been initially opposed to the very

idea of a Constituent assembly, he later realized in the passionate

debates that all this exercise proved not only the evidence of maturity in

the reborn Italian democracy, but also the effectiveness of dialectical

dispute when thinking is the creative factor for political debate together

with social conflict and competition in the economy.

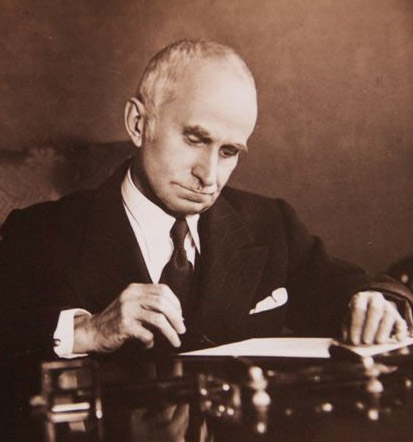

The President of the Republic

Luigi Einaudi was elected President of the Republic on 11 May 1948 at

ballot four, with 518 votes from the Christian Democrats, the Social

Democrats, the Liberal Party and the Republican Party. The Socialists

and Communists supported Vittorio Emanuele Orlando who casted 320

votes. In his swearing-in speech, Einaudi wished to emphasize that the

difficult present derived from a dramatic past: "Twenty years of

dictatorship had served the country with civil discord, external war

together with material and moral destruction to the Fatherland to such

an extent that any hope of redemption seemed vain. And instead, all

these sufferings re-elaborated in the Resistance led to protecting "the

indestructible national unity from the Alps to Sicily", while the

reconstruction of the "destroyed material fortunes" was beginning. Along

the lines marked out by the Constitution, he emphasized the central role

of the Parliament, the place where "true life is, the very life of the

institutions that we freely gave to ourselves" and the need to pacify

souls after the mid-century disaster. With the election of Einaudi,

certainty was given to the organization of presidency: a special Act of

Law defined its endowment and established the General Secretariat of

the Presidency of the Republic, headed by Ferdinando Carbone from

1948 to 1954 , and by Nicola Picella from 1954. In interpreting and

carrying out his function, Einaudi adhered to a profound respect for the

dialectics between the political and the parliamentary forces.

At the same time, within such established boundaries, he exercised the

powers that the Constitution assigned to the President. He claimed and

used the prerogatives that the Constitution had ascribed to the President

of the Republic, even if this could mean on some issues, such as the

power to choose senators for life and constitutional judges, some

contrast with the majority which had elected him. During the years of

Einaudi’s presidency, Italy healed the wounds of the war, made the

fundamental choices for its international position by joining NATO and

the rising European institutions, brought Trieste back in the national

borders, and launched a vast modernisation of economic facilities. After

his term of office ended, Einaudi published Lo scrittoio del Presidente

(The President’s writing desk), a volume collecting letters, memoirs,

observations, and proposals for modifications suggested by the

legislative texts submitted by the government. In the years following

1955, he also published Le Prediche inutili (1959) (Useless preaching)

and many other articles in reviews and newspapers which testify to the

fruitful intellectual activity carried out by Luigi Einaudi until his death in

Rome on 30 October 1961.